‘We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence therefore is not an act but a habit’ – Aristotle

Often the difference between those who succeed and those who do not is the habits they form. This is how we hit peak performance – forming good habits and breaking bad ones.

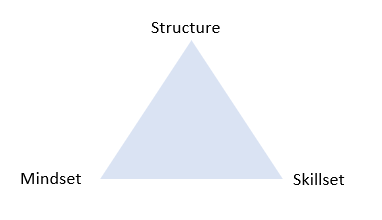

All Blacks mental skills coach, Gilbert Enoka, talks about this in relating his experience of coaching rugby players. There’s a combination of mindset and skillset he says is crucial for success, but there’s also a third, equally important point: structure. Together, mindset, skillset and structure make up Enoka’s success triangle.

He’s witnessed players who have the necessary skills and mindset still fail to make the team because of a lack of structure. If they can’t adhere to the necessary routine of training, early nights, meal plans and habits, they will inevitably not succeed.

Of course, the fact that habits are so important is easier said than done. Often it’s not our lack of knowledge that’s the problem but how we implement the knowledge we do have, especially on a regular basis. Success requires structure, in the form of a succession of positive habits.

Forming good habits sounds simple, but, of course, it’s not. Otherwise, we’d all go to the gym, eat salad all the time and wake up at 6 am every day. Even when we know the negative impacts of a certain habit, it can be hard to break. Think of smoking, for example; we all know it kills us, but sometimes that’s still not enough to stop us.

A habit is a repeated behaviour that becomes automatic. The trouble is that we tend to find it easier to keep the bad habits and harder to form good ones – that involves more effort and less immediate reward.

Our bad habits work against us by being easy to perform and giving us instant reward hits – a wine on a Friday night, for example. Eating well, in contrast, won’t give us an immediate sugar hit, and the health benefits or weight loss might not be evident until weeks down the track.

How can we build positive habits and break bad ones? The best advice I’ve heard on this topic comes from James Clear in his book Atomic Habits. Clear believes that both success and failure are preceded by habits, and that we can be the creator, rather than the victim, of our habits. What’s on our desk or the way we set up our home can influence our behaviours and habits, he says; our environment is the architect of our habits.

What I like about focusing on our habits is that it puts us in control; it’s something we can influence. Whilst we tend to think that success is just down to talent, and that some people are just high performers for that reason, there’s much more to it. Talent gets us so far, but great habits make the difference. It makes sense when we look at those who are truly talented. At some point, those people are going to reach a peak at which everyone else around them is just as talented. At that point, how do they stand out? The answer lies in good habits, continuous improvement and a drive for performance. A lot of top athletes, for example, may have had talent to start with – but so did others who’ve not made it in their field. The difference most of these athletes talk about is the hard work and effort they’ve put in.

Peak performance is about forming good habits and repeating them consistently, whether that’s a gym routine, organising your diary, doing your filing, taking a lunch break or checking in on the team.

Let’s look at breaking bad habits first.

Reducing exposure and temptation is fundamental. If you want to save money, unsubscribe from those marketing emails that tempt you with specials. Want to stop eating chocolate at night whilst watching TV? Don’t buy it or have it in the house. If you have to get in the car and go to the shops for it, you’re less likely to pursue it – making the bad habit harder helps break it. I don’t have biscuits in the house usually; it’s an easy way to break my bad habit of demolishing a whole packet in one sitting.

Is your environment conducive to forming good habits or bad ones? Which habits are easier for you, and how can you make the bad ones harder and the good ones easier? Having my gym kit ready to go in the morning means I’m more likely to go to the gym later that day – in that way, I’ve made the habit easier.

The law of least effort applies, according to Clear. If we succeed in making bad habits harder and good habits easier, we’ll see a shift. We also have to want to create the habit (that is, we have to enjoy it), and we have to have an environment that’s conducive to the habit and a plan to make it happen.

The law of least effort is why it’s easy to binge-watch Netflix. It’s easier to let it keep auto-playing the next episode than to pick up your device and press stop. In this way, when we plan on watching one episode, we often end up watching the whole season and staying up three hours later than we meant to!

This is why I go on retreat to write books. It removes distractions. I find less excuses not to write when I’m away in the countryside, in a cottage, by myself. I don’t have TV and I don’t take books; it’s just me and my writing. I have to make it rewarding, though, so I take my favourite snacks and give myself a target. Each day, when I hit the word count that I’m aiming for, I reward myself with a cup of tea and some chocolate biscuits. That gives me that instant gratification; a reward that comes much sooner than seeing the book on the shelf. In this way, I’m forming good habits and making them easier to adopt.

I love the sauna, but the gym takes a bit more motivation. I go to the gym, and then I reward myself afterwards with a sauna, which is in the same building as the gym. I know I only get the sauna if I go to the gym, and once I’m in the building for one, the other becomes much more doable.

Another great hack from James Clear when it comes to forming good habits is something he calls ‘habit stacking’: adding a new habit we want to form on to an existing habit we already have, so we’re more likely to do it.

As an example, I mean to take my supplements every day, but I often forget. Leaving them by the kettle helps remind me and make this habit easy, because I’ve stacked it with another habit I know I’ll do every morning – my cup of tea.

Similarly, my meditation habit is something I do each morning for 10 minutes at the same time my partner is walking the dog. It means the house is quiet, and it’s part of my routine before my shower.

Thinking about habits can become a drain – the ever-constant thought ‘I must do this.’ Reframing statements like this into ‘the kind of person I want to become’ gives the habit more meaning and also motivates us.

I want to be a calm, clear-headed, happy individual; that’s why I meditate each morning. That self-talk gives me a different way of thinking about the habit; it’s not just another thing on my to-do list I’ve got to get around to doing today. It connects my activity with my ‘why’: the benefit I’m getting from the habit and how I identify myself. It links my results to my beliefs. There’s also the added reward hit my meditation app gives me: a gold star each time I don’t miss a day. Let’s face it, the reward of a calm, clear mind takes much more than one session to realise.

So, what habits do you want to form, and what’s your plan of action?

Having the goal is one thing, but James Clear will tell you that the habit is the system behind the goal: it’s the habit that will make the goal a reality.

Our fitness or weight loss goals only happen because of healthy habits. Our revenue goals are realised because of our sales strategy, so success is less about what we’re aiming for and more about what we’re going to do to get there – then the result takes care of itself.

This knowledge enables us to create a plan and develop good habits. I really like the analogy Clear uses of running a race. We tend to focus on the finish line, and ready ourselves for the result we want to see. But Clear tells us we should focus on being ready for the start line. If we’re ready at the start line, the finish line (the goal) will take care of itself; it will eventuate by virtue of our training and preparation (our habits).

If I’ve already put my gym kit in the car the night before, I’ve already done the hard work; the chances are greater that I’ll work out now rather than turning around and going home.

It’s worth considering how you can make your good habits more achievable and more within your reach, otherwise your goals can become overwhelming. Clear advises focusing on one habit at a time and aiming for a 1 per cent improvement. This is achievable and still impactful as it compounds: Clear calls it the power of tiny gains.

Find out more in the new book, Burnout to Brilliance, out now